The MIT Team That Broke Las Vegas

"They didn't cheat, didn't bribe, didn't break laws—only exploited those same laws to their advantage."

Las Vegas was built to pulse at one emotional frequency: anticipation.

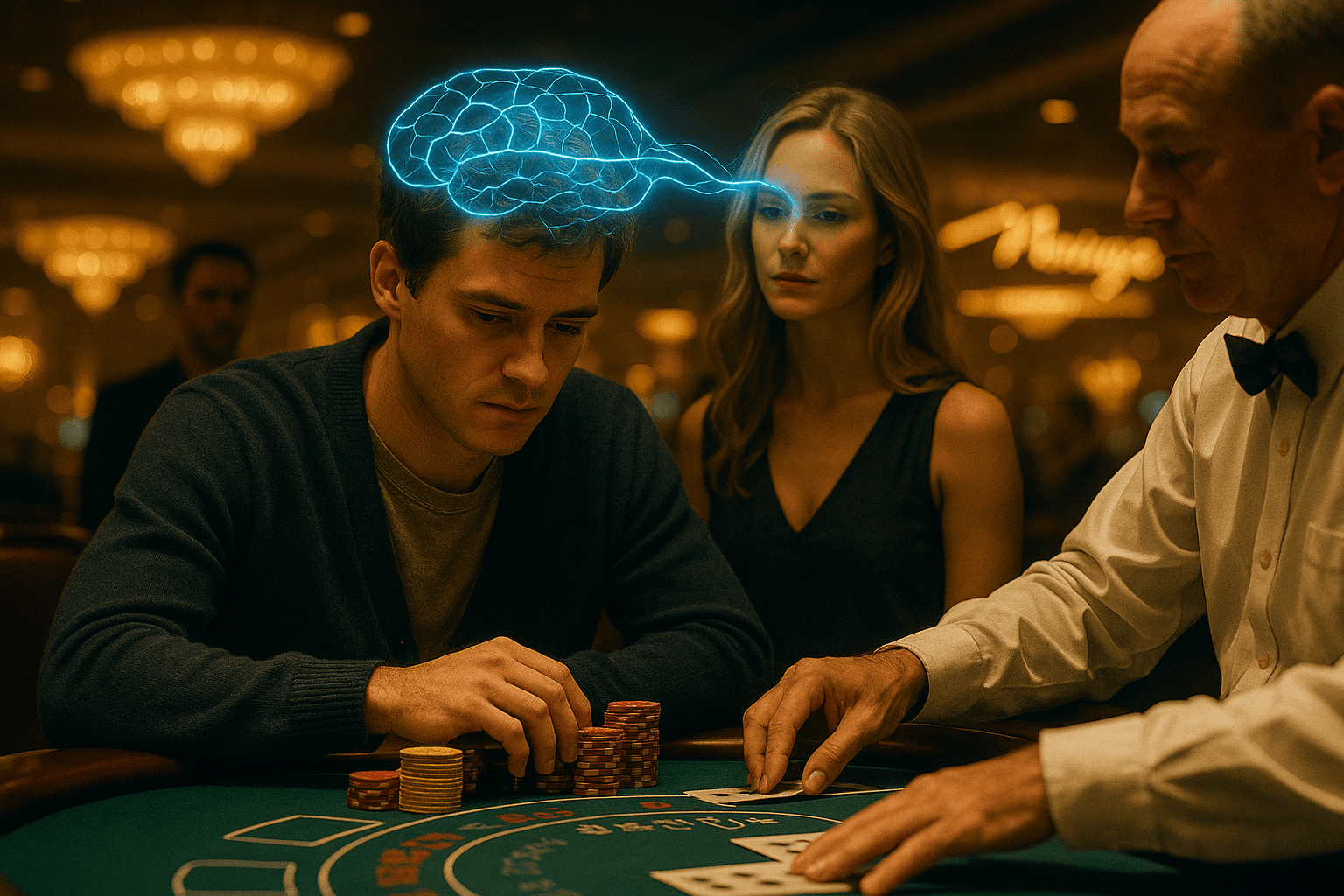

Like any story about a group that broke the casino, it all starts with disguise: beneath the golden, low lighting of the "Mirage" hotel, a young man in an ill-fitting Armani cardigan stares at his chip pile as if solving an equation in his head, or perhaps his gaze was momentarily distracted by a puzzle to the side in one moment of lost concentration, but he quickly returned to business. He observes the dealer's hands moving at a steady, professional rhythm—if this were a movie, we'd be meant to think he's just slick; the cards glide across the green felt with a whisper so delicate it's audible to sharp eyes on the other side of the casino. When the count flips in his favor, he pushes forward a stack worth a full semester's tuition. To the cameras, it looks like just another tourist trying his luck. In reality—this was a planned operation, precise, staged down to the last detail, the product of hundreds of hours of training in MIT dorm rooms in Cambridge.

On nights like these, and hundreds of similar nights in the '80s and '90s, a group of students from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology proved that if you measure luck correctly—it's no longer luck. The casinos called them "counters." They called themselves "the Team."

The hidden language of control — where intelligence meets illusion in Las Vegas.

So What Was the Game-Changing Idea?

Blackjack is almost the only game where

what happened before affects what will happen next. Every card that comes out

changes the probability of the remaining cards. Between you and me, even on

paper, no one can keep track, at least not in a crowded, energetically insane

environment. But the students from MIT succeeded.

After all, at the end of the day, we're not

talking about hacking into a casino or some massive fraud, we're talking about

card counting—that's simple mathematics. When low cards (2-6) come out, the

player's chances improve, because more tens and aces remain in the deck—meaning

more opportunities for a natural 21. Counters assign value to each card: plus one for a low card, minus one for a high card. The cumulative sum—the

"count"—reveals when the odds tip in their favor. When they're

high, they bet more. When they're low—they bet less.

The idea had existed since the '60s, in Professor Edward Thorp's book Beat the Dealer. But what the MIT group understood is that an organized team could exploit the system much better than a single player. The idea is, of course, disguising the real player: there's one counter who tracks the cards and bets small amounts, while his friend—the "big player"—enters the game only when the cards are right. So what happens here: the casino sees a stranger placing high bets in what appears spontaneous, but his entry was coordinated by the small bettor.

"Think of it this way: if the guy who sat and counted cards for a long time and bet small amounts suddenly came in with a large sum, they'd immediately notice him. But he actually continues to play for small amounts, so in the casino's view, he's a legitimate bettor.."

So How Was the System Built?

It all started small—between labs,

libraries, and cafeterias in Boston. The student group played for

experimentation, out of intellectual curiosity, but between us, surely also out

of interest in proving they were smarter than everyone 😊. But by the end of the '80s, they had already become a professional

body operating almost like a real business. They established partnerships,

recruited investors, divided profits, and planned every operational move like a

proper startup company.

The flights under assumed

identities—"Mr. M," "Mrs. R," "the Gorilla"—were

preceded by training. These were intensive and serious training sessions:

counting a full deck of cards in less than 30 seconds, identifying dealer patterns

from the corner of the eye, and maintaining a calm expression even when

security guards are looking directly. They knew that any slight hand tremor

could cost thousands of dollars, and that there's no room for real excitement

because that's exactly the stage where mathematics loses its power.

And that's how the system worked, because it essentially didn't rely on luck or the number of attempts to succeed—they built a method, and methods succeed when they're fundamentally correct, but also when the people executing the method are themselves professionals. That's how skilled teams do the impossible, because they broke down the model of a single bettor who can be identified.

How Did the Casinos React?

Every success attracts attention; actually,

it's more accurate to say: recurring patterns are discovered. Just as skilled

naturalists identify patterns and then investigate what enables those patterns,

so in the early '90s, Las Vegas security teams began identifying patterns. At

the end of the day, security teams themselves are a very serious body. And they

started identifying: small player exits, big player enters, table empties,

money changes hands. The casino has monitoring systems, money doesn't just change hands randomly, and there are long-term statistics. When there's one or two anomalies, that's part of the business, but when there are dozens, that's already an anomaly requiring investigation. But even before the

investigation, casinos shortened game duration, introduced automatic shuffling

systems, and employed their own mathematicians.

The casino's advantage is that it doesn't

have to find the breach to prevent it; it can narrow it by changing systems.

And the nineties became very technological years anyway. And when facial

recognition technologies arrived, the game became an early artificial

intelligence war. Some team members grew beards, changed hairstyles, and adopted

new accents. Some were forcibly expelled, others were blacklisted from all

Vegas player lists. Some moved to play in Atlantic City, the Bahamas,

Canada—anywhere the laws were softer.

The new systems gave casinos tremendous power. Security teams learned to think like engineers, not like gatekeepers. They turned gambling into a data laboratory—every card, every movement, every expression measured.

In a sense, both sides—both the casinos and the students—became mirror images of each other: two mechanisms trying to control randomness, each in their own way. That's the way of the world: new knowledge in professional hands becomes an efficient tool. But the world is a large system of interests, and knowledge itself changes hands, and in the case of large casinos, they themselves can buy the knowledge and thereby close the loopholes.

So Did They Enjoy the Double Life?

Behind the large sums of money and success

was ultimately deep exhaustion. Team members led double lives—students

mid-week, professional gamblers on weekends. At first, it's always exciting, but over time, it becomes a routine that demands a lot. And as the operation expanded, more money came in, more people, more

secrets—and the balance between private life and secret life broke down.

Most dealt with an enormous burden: regular

flights, constant tension, sleepless nights, and the need to maintain a fake

identity for months. Some earned hundreds of thousands of dollars, some even

lost huge sums in unsuccessful rounds. The work and stories about failures and

successes began creating tensions within the team—who worked harder, who

received a smaller share, and who reported truthfully about profits. In addition to

everything, accusations began, suspicions, and fights that dissolved

partnerships. And again, it's not enough to be a professional in your disguise;

there's the need to know how to manage good partnership relationships with your

partners. And that's perhaps something important to take from this story.

Because the problem intensifies when you consider their personal relationships. Because to maintain secrecy, many didn't tell their spouses or families what they were really doing. And they were indeed professionals, but not everyone can live a double life; that already requires a different psychology. That's what enables spies to succeed, but to be both a spy and a mathematician, and to discover that your work is to spend hours upon hours in casinos, but... and this is a big but... you're not actually allowed to enjoy it. These things cause material fatigue. So maybe another thing to learn is to know when to stop and take a break. And not to think every moment about "how much I could make" or perhaps enter into jealousy games with partners.

After all, the casino is meant not just for

gambling but for having fun, and a fun atmosphere is a freer atmosphere, one where it's hard for us to be serious for hours. And that's a more

difficult mental battle. In the casino there's lighting that simulates

daylight, music that suppresses fatigue. After twelve hours, counting becomes

difficult, unbearable, and frustrating. The dealers on their side rotate, they

rest, and they don't disguise themselves. In addition to the dealers, the

cameras always work, and that ultimately starts getting into your blood, and

every decision that in the first hour is considered and easy becomes as

sensitive as if it's both choice and fate.

They called it "playing a character"—but for some, after a few years, the character simply swallowed the person. And that's the completion of the full circle: they ultimately became addicted!!!

So What Happens When the Advantage Flips

In the mid-'90s, the team's original core began to disintegrate. Some players formed new groups, others tried to refine the system using advanced counts, computer simulations, and shuffle-tracking techniques.

But as the system improved, it emptied of

meaning.

The game, which had started as a combination of mathematics, intuition, and daring, became, thanks to their technique and skill, a mechanical routine. Every decision seemed predictable, every risk calculated in advance. The tension between logic and uncertainty—that excitement that attracted them initially—disappeared. The players themselves started getting bored with the game. Which is amazing, they actually say this. Which is amazing because it's exactly the opposite of what we talked about in articles like the Illusion of Control—those who actually succeeded in achieving control lost the meaning of the game. The illusion at the beginning of the road was actually of the casinos that didn't know there was a way to beat them.

" But ultimately there's something very interesting in us as humans: we always want to know everything, but when we know everything we're simply bored, like watching the same movie over and over."

And this, over and over, led some of them to leave quietly, return to studies, or move to the financial world, where there was still room for a sense of control within chaos. Others stayed, convinced that if they just improved the model further, they'd succeed in calculating even the unpredictable.

But deep inside, they already knew: the game was over, not because they lost—but because there was no longer anything to win. The feeling died inside them, and the casinos changed the rules.

So What Did They Prove?

Mathematically, their success is clear: for over a decade, they earned millions—legally. The casinos won in the end, not through lawsuits, but by changing reality itself. They changed the game until mathematics no longer worked. Actually, you could say that if the casinos hadn't changed the rules, they couldn't have continued letting players play blackjack, certainly not in the AI era!

Ultimately, the MIT team didn't just beat the game—it exposed the paradox on which the entire gambling world stands.

The line between skill and manipulation

turned out to be much thinner than it seems.

The casino presents itself as a kingdom of luck—a place where everything is random and everything is possible. But in practice, it's planned down to the last detail: the lighting, the sounds, the carpet smell, the rhythm of dealer changes. Every detail is designed to keep the player tense, focused, and emotionally "close to winning." The feeling of being close to winning, as we saw in "The 'Near-Win' Effect in Slot Machines," is part of the system that sells self-control—but controls consciousness.

On the other hand, the counter team used cold intelligence to regain control to themselves. They didn't cheat, didn't bribe, didn't break laws—only exploited those same laws to their advantage. But they too built an illusion: a secret theater of probability, where they played the role of absolute control within measured chaos.

Both sides essentially sold the same promise—the illusion of control.

That is, to be precise, the casino's illusion of control is toward the players; it makes the player think they can beat the system.

The MIT group's illusion of control was toward the casino, that if the casino had known from day one there was a system, it would have immediately rendered the mechanisms to cancel it.

But the casino truly controlled. It set the rules, the probabilities, and the psychological conditions that keep players alert and tense. The casino didn't gamble—it managed the system.

The team, on the other hand, created a different kind of control: control within the boundaries of the arena the casino defined in advance. They didn't break the system; only learned how to breathe between its cracks.

In this sense, they proved something deeper than money or victory:

When you try to eliminate luck, you also eliminate freedom.

The attempt to control every probability, every outcome, turns you into a mechanism.

In the end, the system they built to beat the game became the game itself—

and they became players within the rules they created. Years later, many of the players said they were less interested in the money, and more in the experience. It started as an intellectual experiment—and ended as an understanding of what it means to be human: we need uncertainty to truly live. But to beat the system, they had to become it, and they forgot themselves along the way. But some still remember the money to this day 😊

After the End

"The film wrapped reality in Hollywood gloss. But the real team members told a different version: less glamorous, more grinding."

Some team members went on to brilliant careers in finance, data, and technology. Others disappeared from the radar.

Years later, Hollywood discovered the story and turned it into the film "21" (2008), directed by Robert Luketic.

The film, inspired by Ben Mezrich's book Bringing Down the House, depicted a dramatic and polished version of the MIT team that counted cards and succeeded in defeating the Las Vegas casinos.

In the lead role appeared Jim Sturgess as Ben Campbell—a fictional character based on the real student Jeff Ma. Alongside him played Kevin Spacey as a cold and manipulative professor who forms the team, Kate Bosworth as his smart and mysterious partner, and Laurence Fishburne as the tough security man trying to expose them.

The film wrapped reality in Hollywood gloss—glittering cinematography, electronic soundtrack, dialogues full of confidence.

But the real team members told a different version: less glamorous, more grinding.

In reality, it wasn't a story about glory—but about constant pressure, about double identities, and about one big moral question:

What happens when perfect control becomes a new kind of gambling?

So what was their real innovation? It wasn't blackjack—but the way they turned thinking into a team sport. They showed that intelligence can be organized, that discipline can beat luck, and that even within the chaos of Vegas you can find a moment of order—a moment, and no more. But what they still lacked was: they weren't really spies, their psychology didn't allow them to live the double life as if they were normal lives. And so we return as always to the fact that in gambling, the psychological element is critical.

But We'll Of Course End with Lights On!

The MIT group showed the world that every system can be learned, every pattern is identifiable. But they also discovered that information demands a price: the moment luck becomes predictable, the magic disappears.

But... Las Vegas, indifferent as always, continues to shine even at night. And the cards continue to fall.

And the edge—that imperceptible half-percent of control—continues to glimmer, just beyond reach.

And perhaps it's really better that in most cases it remains beyond reach.